Information Paradigms and Radical Interfaces

Posted 6/16/20

One of my non-social-org interests is the design of interfaces for viewing and interacting with information that can change our perception and thought-processes surrounding that information. I haven’t written much on this subject yet (except tangentially when discussing Halftone QR Codes to create dual-purpose links/images), so this post will be an overview of information paradigms and exciting ideas in the topic space.

Conventional Model: Folder Hierarchies

When computers were imagined as information storage and retrieval systems, they first replaced their physical predecessors: Filing cabinets filled with nested folders. This hierarchy describes every major “filesystem”, including directory trees on Unix/Linux and Windows:

However, a simple hierarchy fails to describe information that belongs in multiple places at once: What if a file could be categorized under “Research” or under “Gradschool”? We can address this problem with links or aliases (so the file is in the “Research” folder but has a reference in the “Gradschool” folder), but it’s an imperfect solution to an awkward shortcoming.

Predominant Internet Model: Hypertext

While a folder hierarchy allows one file to reference another, it does not allow for more sophisticated referencing, like a file referring to several other files, or to a specific portion of another file.

Both of these problems can be improved with hypertext, which introduces a concept of a “link” into the file contents itself. Links can refer to other documents, or to anchors within documents, jumping to a specific region.

Hypertext is most notoriously used by the World Wide Web to link between web pages, but it can also be used by PDFs, SVG files, and protocols like Gopher. Still, there are more sophisticated relations that are beyond hypertext, like referring to a region of another document rather than a specific point.

Xanadu

Ted Nelson’s Project Xanadu aimed to extend hypertext dramatically. Xanadu departed from the idea of static documents referencing one another, and proposed dynamically creating “documents” out of references to information fragments. This embedding allows bidirectional linking, such that you can both view a piece of information in context, and view what information relies upon the current fragment. The goal was to allow multiple non-sequential views for information, and to incorporate a version control system, so that an information fragment could be updated and thereby update every document that embedded the fragment. Information storage becomes a “living document”, or a thousand living documents sharing the same information in different sequences and formats.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, Xanadu’s scope has hindered development for decades. A subset of Xanadu allowing embed-able fragments can be seen in a demo here. The bidirectional-reference model struggles to mesh with the decentralized reality of the Internet and World Wide Web, and a central database for tracking such links is impossible at any significant scale. HTTP “Referer” headers ask browsers to notify web servers when another document links to one of its pages, but the system was never widely deployed as a way of creating bidirectional links. Tumblr and Twitter “reblogging” and “quote retweeting” comes closer by creating bidirectional references, but falls short of the living-document paradigm. Wikipedia accomplishes bidirectional links within its own platform, and allows anyone to edit most pages as they read them, but still considers each page to be independent and inter-referential rather than dynamically including content from one another to create shifting encyclopedic entries.

Some projects like Roam Research continue developing the Xanadu dream, and support embedding pieces of one document in another, and visualizing a network diagram of references and embedded documents. There’s a good writeup of Xanadu’s history and Roam’s accomplishments here.

Explorable Explanations

Linking information together between different fragments from different authors is an insightful and revolutionary development in information design; but it’s not the only one. Bret Victor’s essay Explorable Explanations provide an alternate view of information conveyance. It critically introduces the concept of a reactive document, which works something like a research paper with a simulation built in. Any parameters the author sets or assumptions they make can be edited by the reader, and the included figures and tables adjust themselves accordingly. This provides an opportunity for the reader to play and explore with the findings, develop their own intuition about how the pieces fit together. There’s an example of this kind of interactive analysis at Ten Brighter Ideas.

Visual Exploration: XCruiser

All the models so far have focused on articles: organizing articles, moving between articles, synthesizing articles out of other articles, and manipulating the contents of articles. Other paradigms move more radically from simulating sheets of paper.

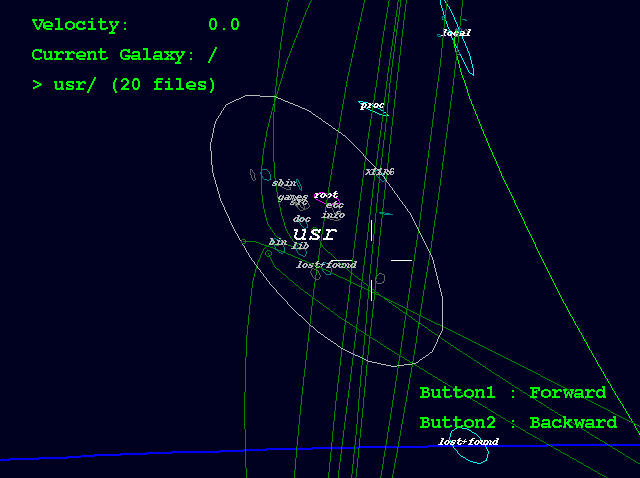

One such paradigm is XCruiser, which renders filesystems as three dimensional space. Directories are concentric galaxies, while files are planets. The user literally “flies” through their computer to explore and can see parent, child, and parallel directories in the distance.

It is, perhaps, not an intuitive or particularly useful model. Nevertheless, it demonstrates that our classic “hierarchical” view is far from the only possibility. A similar 3-D filesystem renderer is FSV, the File System Visualizer, featured in Jurassic Park.

Kinetic Exploration: Dynamicland

Finally, interfaces need not be purely visual, reached through a monitor, keyboard, and mouse. Bret Victor’s most recent and daring project, Dynamicland seeks to reimagine the boundaries of a physical computer. Terribly oversimplified, the idea is:

-

Strap a number of projectors and cameras to the ceiling, aimed at the floors and walls

-

Give the computer OpenCV to recognize objects and read their orientations and text

-

Program the computer to display information via any projector on any surface defined by physical objects

-

The entire room is now your computer interface

Ideally, the entire system can be developed from this point using only physical objects, code written on paper, a pencil on the table turned into a spin-dial referenced by a simulation on the wall. No screens, no individual computing.

The main takeaway is that the computer is now a shared and collaborative space. Two computer-users can stand at a wall or desk together, manipulating the system in unison.

Almost all our computing technology assumes a single user on a laptop, or a smartphone. We put great effort into bridging the gaps between separate users on individual machines, with “collaboration” tools like Google Docs and git, communication tools like E-Mail, IRC, instant messaging, slack, and discord. All of these tools fight the separation and allow us to compute individually and share our efforts between computers, but Dynamicland proposes a future where a shared space is the starting point, and collaboration emerges organically.